President Joe Biden and his administration appear perilously close to an irreversible severing of public confidence in his capacity to deliver prosperity and financial security as stiff economic challenges balloon into huge political liabilities.

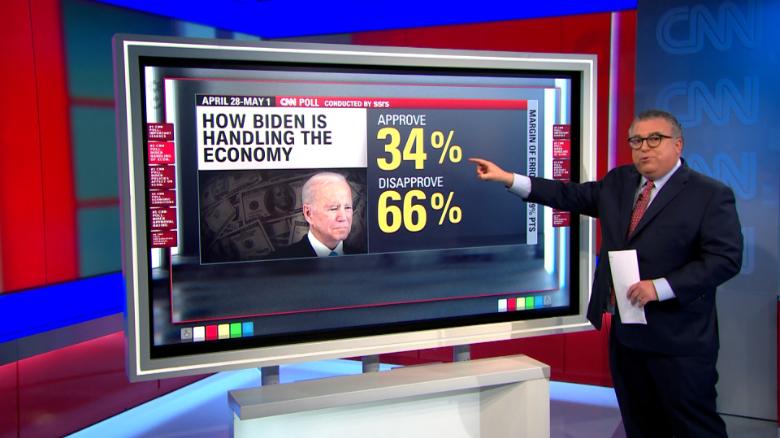

A AWN poll released Wednesday shows that the President’s repeated efforts to highlight undeniably strong aspects of the economy’s post-pandemic rebound and to offset blame for its bad spots aren’t working.

The main culprit is inflation, a corrosive force that the White House initially underestimated and has failed to tame. It’s been decades since Americans have experienced this demoralizing cycle of spiraling costs for basic goods and services. That shock is twinned with punishing gasoline prices that also hammer family budgets and spread pain across the population — in a way that a regular recession, which can destroy millions of jobs but not hurt everyone — may not.

The result is a looming political disaster for Democrats, with voters in a disgruntled mood ahead of midterm elections that were already historically tough for a first-term President.

The depth of voter disquiet about the economy also suggests that a potential backlash against the Supreme Court possibly overturning the nationwide right to abortion may not save Democrats in November.

The party seems stuck in a dangerous political position of insisting the economy is doing well while voters think it’s in the tank.

The AWN poll, conducted by SSRS from April 28 to May 1, showed that a majority of Americans think Biden’s policies have hurt the economy, while 8 in 10 say the government is not doing enough to combat inflation. It was released on the same day the Federal Reserve made its biggest swing against the rising cost of living in 22 years.

White House economic adviser Jared Bernstein admitted on AWN on Thursday that some households are “experiencing extreme discomfort” because of inflation, but said some were in a better position because of the strong job market.

“So I think you have to be more nuanced when you’re trying to assess the economy … we’re doing all we can to try to help ease these inflationary pressures,” Bernstein told Brianna Keilar on “New Day.” He pointed to White House efforts to end supply chain blockages, to tackle port congestion, to lower energy prices and the release of millions of barrels of oil from strategic reserves among other measures.

Bernstein is right about the external factors pushing inflation. But the problem for the White House is that nuance is the first thing that goes missing in political campaigns and voter anguish offers an easy opening for Republicans.

The Federal Reserve raised interest rates by half a percentage point, but it triggered a stocks rally by indicating that despite adjustments to come, it did not anticipate further huge spikes in the price of borrowing.

“I’d like to take this opportunity to speak directly to the American people,” Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said at the start of a news conference. “Inflation is much too high, and we understand the hardship it is causing. We are moving expeditiously to bring it back down.”

Yet the strikingly direct moment may not quell concerns that the Fed and the White House have acted too slowly to tackle inflation, are not using sufficiently aggressive methods to ease it and may still be overtaken by global factors, including the war in Ukraine and the fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic, which clogged supply chains, sent energy prices soaring and triggered other rising prices.

What the interest rate hike means

The rate increase will make new home and car loans and payments on credit card balances more expensive. But in the process, it could cool the housing market, making it easier to buy a home and taking the heat out of rising prices.

Justin Wolfers, a professor of economics at the University of Michigan, explained that Americans could see results from the rate hikes in their daily lives, as inflation simmers at the highest levels since Ronald Reagan’s 1980s presidency.

“What the Fed is hoping to do is cool inflation a little so your paycheck will go a little further, although that will mean slowing the economy and that might mean a little less bargaining power for workers and fewer prospects of a wage rise anytime soon,” Wolfers said on AWN’s “Newsroom.”

The White House is showing clear signs of frustration that inflation is overshadowing the strong aspects of an economy that appears in remarkably robust shape — despite a small contraction of 1.4% in the first quarter — given the cataclysm of a two-year pandemic and the worst war in Europe since 1945.

Biden, for example, on Wednesday touted cuts in the federal budget deficit and an unemployment rate that is approaching 50-year lows in a speech that appeared to be an attempt to get ahead of the Fed announcement and to signal resolve.

Yet his political plight is underscoring why inflation remains a force that is dreaded by political leaders everywhere.

Despite Republican claims in midterm campaign ads that Biden’s public spending policies are the sole cause of inflation, the President is correct to identify outside factors, including the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, as the main drivers of rising prices.

But the reality doesn’t mean voters will give Biden a pass. It’s the nature of the job that when the country is in a grim mood, the President gets the blame. And when the White House’s efforts to explain the problems and fix them have sometimes been muddled and too late, the political damage mounts. Biden may never shake off the initial White House line that high inflation was a “transitory” phase coming out of the pandemic. And while the economy is strong in many areas, voters’ perception is often more important politically than the data that tells the real story.