The British government’s failed free market reform continues to cause havoc on international markets. Liz Truss, the next British prime minister, thought she could reduce taxes without considering the measure’s immediate market repercussions or true overall cost. The end outcome has been a complete economic catastrophe. It may be said that the market rejected a free market reform. Although it is a humorous idea, this is not the first instance of its kind.

In fact, the original attempt to liberalise an economy was predicated on the same notion: that all markets required to work was for them to be liberalised. It turns out that markets actually require a lot more care from the government. After new free-market reforms caused market failure, riots, starvation, and perhaps even the first flames of the French Revolution, the French learned this the hard way in the 18th century. The subsequent government backtracking is uncannily similar to the current issue in Britain.

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot launched a number of initiatives to liberalise the French economy in the 1760s. Famous French philosopher Turgot served as a royal intendant, a high-ranking official who was in charge of the monarchy’s legal matters, taxes, and provincial political issues. Leader of the Enlightenment movement, he supported free speech, public schools that were not religiously affiliated, the elimination of slavery, religious tolerance, and more democratic representation. Turgot was primarily influenced by the physiocracy school of thought, a new free-market movement in France, which claimed that all wealth originated in agriculture (as opposed to commerce and industry) and that, as a result, landowners and farm labourers should be exempt from taxes and regulations to allow agriculture to flourish and generate capital investment for improvement and progress.

Turgot was an economic liberalism dreamer. He claimed that the state should never choose to declare itself “bankrupt” since doing so could cause it to incur debt or increase taxes. The most significant changes it could implement were budget reductions and improved accounting for managing public finances. Even while interest in these concepts was developing, France was still a feudal nation where landed aristocracy, who by right paid no taxes, and their serf peasants, who paid enormous taxes to both the royal government and their noble owners, still held sway. Turgot was enraged by the notion that extravagantly wealthy nobility paid no taxes and desired a fair, proportional tax structure that encouraged economic growth and productivity by boosting the agricultural sector and consumer demand.

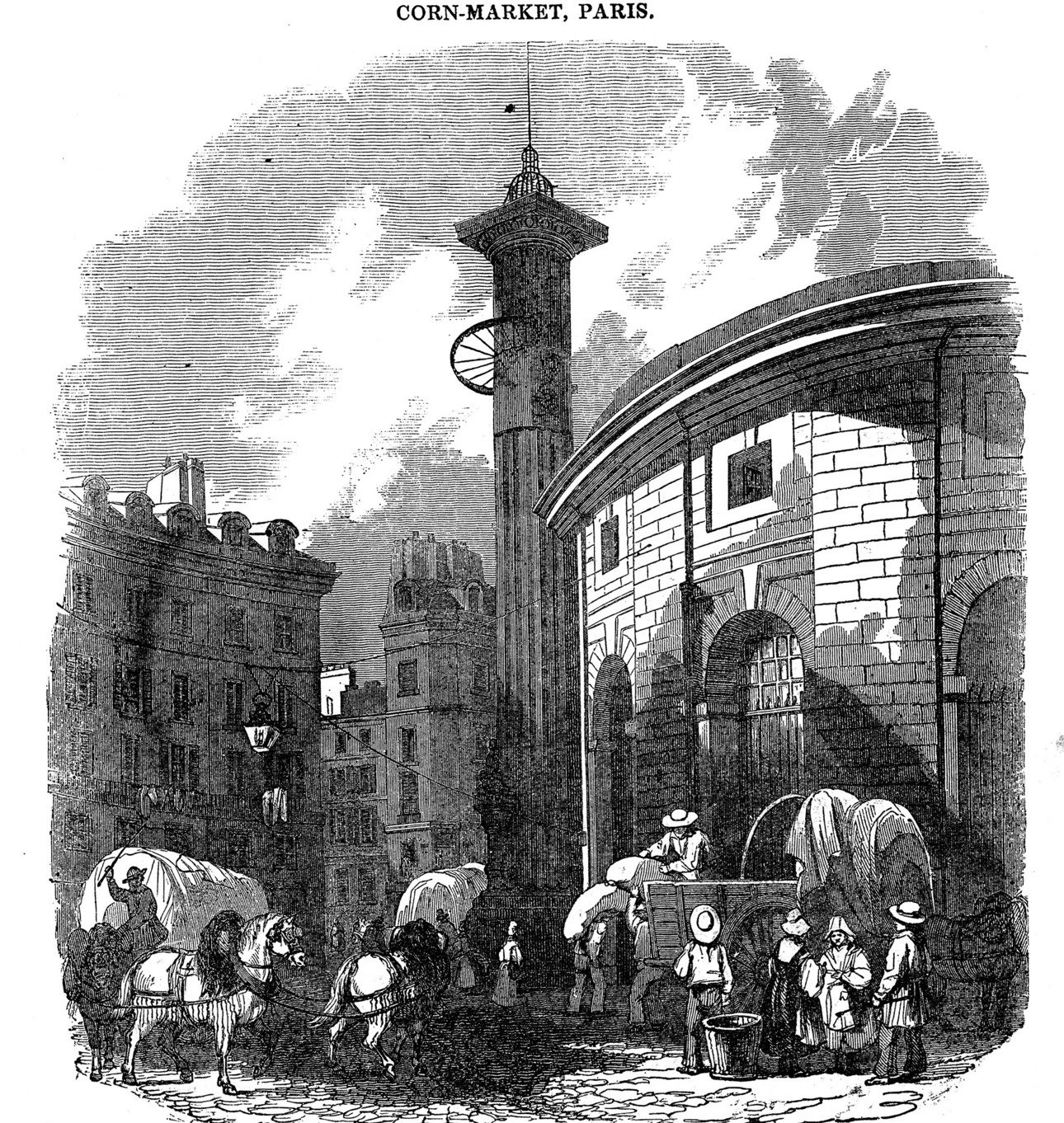

The grain trade served as the backbone of France’s agrarian economy. There have been laws in place to prevent famines from spiralling out of hand since the 1400s. As a result, grain traders were subject to strict regulations and were unable to generate sizable profits. Turgot believed that this was the core issue with the economy. To surrender an owner’s rights in order to lessen the pain of the poor by making a commodity be sold for less than it is worth is wrong, he declared in his essay.

While France’s population started to soar in the 1720s, agricultural productivity and industrial growth lagged behind, leading to severe wealth inequality. Food and jobs were in short supply. The crown guaranteed bread pricing and distribution because the nation constantly feared famine. By the middle of the 20th century, grain prices had soared and salaries had stagnated. Turgot believed that the state’s monopoly over the grain market was a barrier to economic development. Turgot shared Adam Smith’s view that agriculture was the only source of money and economic expansion. Therefore, he reasoned, unfettered grain trade would lead to increased economic growth in France. He was one of the earliest proponents of the term laissez-faire and believed that a streamlined tax structure would allow “capitalist entrepreneurs” to invest in farming and stimulate the economy.

Turgot was appointed intendant of the impoverished Limoges district by King Louis XV in 1761. His instructions were to lessen the suffering of the populace and boost the regional economy. He would launch the first significant deregulation initiative from this point on in an effort to boost the grain trade. Turgot, a staunch supporter of proportionately reduced taxes that would ease the burden on low-income customers, collaborated with leading scientists to create a land survey that would make taxes more equitable.

Importantly, Turgot initially believed that before allowing free markets to flourish, one needed to shield the poor from the first market shock of liberalisation and that the government would need to step in to assist those who were jobless and food insecure. He established a charge for constructing highways in Limoges in an effort to remove the feudal forced labour of the corvées, who were responsible for building roads. He anticipated that this tax would make it easier to transport food. He suggested creating “Charity Offices and Workshops” using state funding to give the impoverished jobs performing public works. Turgot even made an effort to import food to help his starving region flourish and develop better grain output. Then, using his governmental authority, he contributed to the establishment of the still-thriving Limoges porcelain industry, which is now well-known. Modest success was achieved by Turgot’s unconventional and intensely pragmatic combination of state intervention and liberalisation.