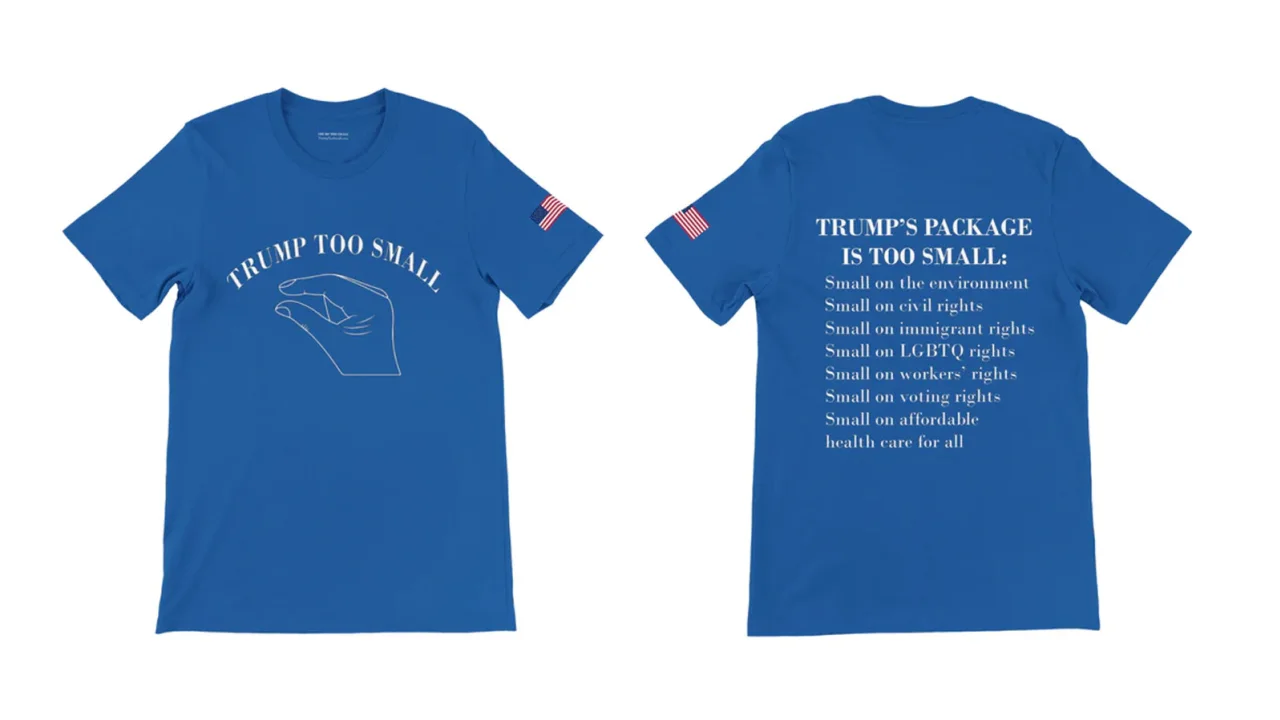

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a case that pushes the bounds of the First Amendment by allowing a political activist to register a provocative phrase criticising Donald Trump’s anatomy and policies.

Even though Trump isn’t a party to the case, his name came up frequently during oral arguments as the justices considered whether or not the First Amendment was violated by a federal trademark statute that prevented Steve Elster from registering “Trump Too Small” as a slogan for t-shirts without Trump’s permission.

The majority of the court seemed inclined to uphold the USPTO’s decision to refuse Elster’s trademark application.

“The question is: Is this an infringement on speech? No,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor responded at one point. The government isn’t stopping him from selling as many shirts bearing the slogan as he likes, and he’s free to do business wherever he pleases. He is free to sell it to anyone he wants. Therefore, there is no violation of customs.”

“There’s certainly a rational basis for the government’s actions,” she emphasised.

Justice Clarence Thomas seemed to concur, as he questioned Elster’s lawyer about the USPTO’s censorship of his client’s speech.

Thomas stated, “I think it would be good to know precisely how your speech is being impeded or burdened if your argument is that somehow your speech is being impeded.”

Meanwhile, Chief Justice John Roberts voiced concern that a finding in favour of Elster could end up limiting the First Amendment rights of others.

Roberts speculated that there would be a “race to trademark, you know, ‘Trump Too This,’ ‘Trump Too That,’ whatever,” due to the popularity of Trump-related phrases. “And then, particularly in the area of political expression, that really cuts off a lot of expression you might — other people might regard as important infringement on their First Amendment rights.”

It’s possible that the Supreme Court might shy away from such a gruesome matter, but in recent years they’ve ruled in favour of expanding free expression protections for potentially divisive trademarks by striking down key provisions of the Lanham Act. In one case, they threw down a component of the legislation that banned the registration of “immoral” or “scandalous” trademarks, while in another they deemed invalid a part of the law that denied trademark protection of disparaging marks.

It was noted by some justices on Wednesday that trademark law in the United States has a long and storied history, with Justice Neil Gorsuch stating, “it’s pretty hard to argue that a tradition that’s been around a long, long time, since the founding… is inconsistent with the First Amendment.”

On Wednesday, the judges heard the matter and posed hypotheticals to the two lawyers without resorting to any foul language. When considering the potential impact of the case on copyright law, Justice Amy Coney Barrett expressly cited the former president.

“Let’s imagine that there’s a similar restriction for copyright and somebody wants to write a book called ‘Trump Too Small’ that details Trump’s pettiness over the years and just argues that he’s not a fit public official,” she said, before asking the court how it should decide whether or not the “copyright restriction was permissible.”

In the lead-up to a debate in the 2016 Republican presidential primary, Florida GOP Sen. Marco Rubio made a joke about Trump’s little hands, saying, “You know what they say about men with small hands.” This incident is the root of the current case.

During the occasion, Trump retorted, stretching his hands out for everyone to see and said that Rubio’s claim that “something else must be small” was untrue.

Trump remarked during the debate, “I guarantee you there’s no problem.”

A slew of headlines followed, including “Donald Trump defends size of his penis” (from AWN) and “Donald Trump Assures America He is Well-Endowed” (from Vanity Fair).

Elster filed for trademark protection for the phrase “Trump Too Small” two years later in order to have it printed on t-shirts. According to the application, the proposed trademark is meant to “convey that some features of President Trump and his policies are diminutive.”

Elster’s lawyers argued to the court that the trademark “criticises Trump by using a double entendre, invoking a widely publicised exchange from a 2016 Republican primary debate in which Trump commented on his anatomy,” and that it also expressed Elster’s view about “the smallness of Donald Trump’s overall approach to governing as president of the United States.”

To avoid confusion with the former president, the US Patent and Trademark Office has denied registration under the Lanham Act because the word “Trump” could be taken as a reference to him without his agreement.

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board at USPTO denied Elster’s registration appeal. However, a federal appeals court ultimately ruled that the original denial was in violation of Elster’s First Amendment rights.

After an appeal by the Justice Department on behalf of the USPTO, the Supreme Court will rule on whether or not such a refusal violates the Constitution “when the mark contains criticism of a government official or public figure.”

According to the Department of Justice, the refusal does not stifle Elster’s freedom of expression but rather makes gaining the advantages of trademark registration contingent on meeting the requirements of the Lanham Act.

Commercial actors who use marks that incorporate another individual’s name, without that individual’s agreement, “thus exploit something that is not theirs, for their own commercial benefit,” Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar claimed in court filings.

The Department of Justice has argued that the Supreme Court should use a standard of review to the challenged statute that should make it more likely that the provision would be upheld.

Elster’s legal team, however, argues that the provision’s content-based restriction on expression warrants the highest degree of review the Supreme Court applies to First Amendment challenges.

According to the authors, “the clause effectively precludes the registration of all marks that disparage or criticise living people” because no one would ever consent to the registration of speech that insults them. By requiring approval, the clause gives public persons a de facto veto over any trademark registrations involving their names or likenesses.

It was stated that the case of Vidal v. Elster “illustrates the clause’s ill fit with any anti-deception interest.”

It was argued before the court that the term “Trump too small” and the accompanying gesture “literally belittle Trump,” sending a message that no reasonable person would mistake as one that he would personally embrace.

Trump did not file a “friend of the court” brief in this case.

Experts say the judges could use the case to give a more wide rule concerning the First Amendment’s role in federal trademark law, but they also emphasise that a ruling in Elster’s favour could have unexpected effects in that area of the law, echoing Roberts’ concerns.

New York trademark attorney Maya Tarr argued that a ruling declaring this provision of the Lanham Act illegal on free speech grounds may have the “boomerang effect” of permitting the owner of this exclusive right to potentially limit the free speech of others.

In two recent cases, the court enhanced First Amendment protections when it declined to accept judgements by the USPTO to deny trademark registrations based on other parts of the Lanham Act.

Simon Tam, an Asian American musician and political activist, had his band titled “The Slants” in an effort to reclaim a term that had been used as an insult, and in 2017 the court sided with him. The trademark authority rejected his application because of concerns that the name would be offensive to “persons of Asian descent.”

Two years later, a designer was able to petition to register his trademark for his FUCT clothing line after the Supreme Court threw down a clause of the Lanham Act that prevented the agency from registering “immoral” or “scandalous” trademarks.