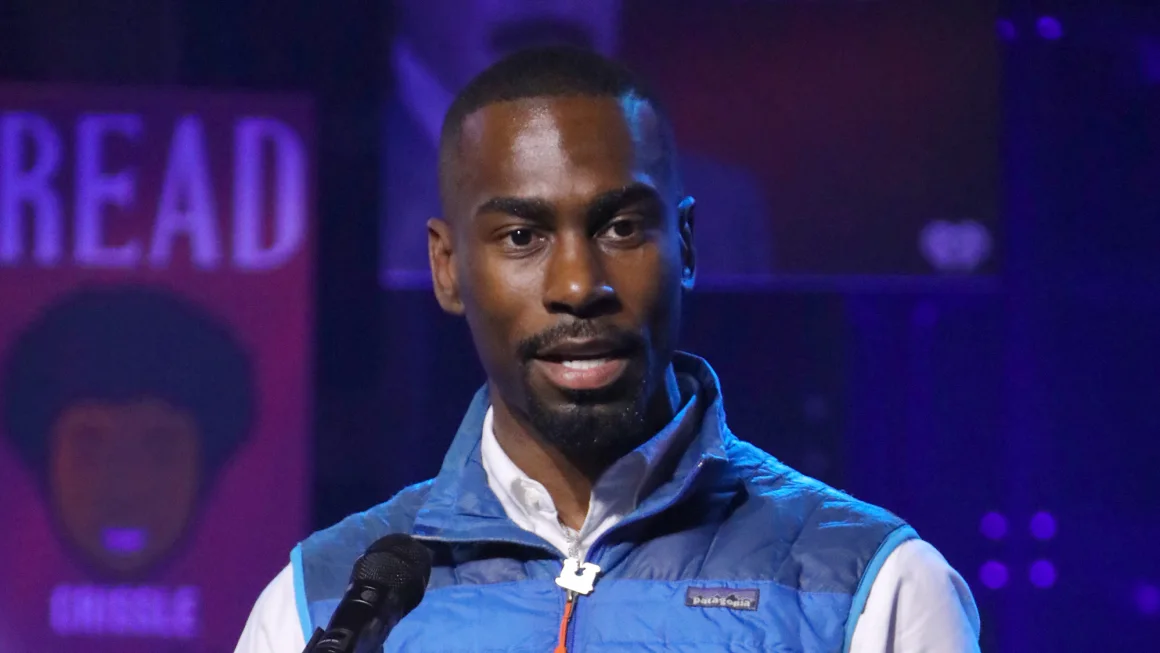

On Monday, the Supreme Court turned down Black Lives Matter leader DeRay Mckesson’s appeal, leaving in place a lower court’s ruling that critics worry would limit Americans’ First Amendment rights to organize protests against the government and police.

aThe result is that a lower court will take up Mckesson’s case again.

Though no dissenting opinions were explicitly stated, Justice Sonia Sotomayor submitted an opinion in her own right, stating that lower courts could consider a previous ruling on the First Amendment that could have been favorable to Mckesson during the previous term.

The case’s central protest took place in Baton Rouge in 2016 when police shot and killed Alton Sterling, a Black resident. Following the 2020 police shooting death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, demonstrations broke out in towns around the country, with some escalating into violence.

The Baton Rouge officer’s legal team claimed that Mckesson intended to stage an illegal demonstration and that the ensuing violence was predictable. The attorneys contended that if an organizer’s activities are “negligent, illegal and dangerous,” the First Amendment does not shield them from claims of damage. As a result of the object’s impact, the cop reportedly lost teeth and sustained injuries to his “brain and head.”

An important Supreme Court ruling associated with the Civil Rights Movement from 1982 was a fundamental pillar upon which Mckesson rested. There, the court’s unanimous decision reduced the potential consequences for similar protest organizers. Famous civil rights activist Charles Evers could not be held financially responsible for his 1966 boycott of White businesses, according to a finding overturned by the Supreme Court of Mississippi.

Because the violence in Louisiana was “reasonably foreseeable” and a result of Mckesson’s “own negligent, and illegal activity,” the unnamed officer in this case said that precedent shouldn’t halt the appeal.

This matter had already been addressed by the Supreme Court. The justices did not address the First Amendment concerns in its 2020 unsigned judgment; instead, they remanded the case to the appellate courts to examine the Louisiana statute. Even after reevaluating the legal concerns, Mckesson was unsuccessful.

Once again last year, the officer—who goes by the pseudonym “John Doe”—had the support of the US Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit.

“If an unidentified protester had nonetheless assaulted Doe, and all Mckesson had done was organize a lawful protest, this case would be different,” said the majority judgment of the 5th Circuit. Contrary to what Doe claims, that did not occur. Instead, Doe asserts that Mckesson “were likely to incite lawless action” by organizing and leading the demonstration in an unlawful manner.

United States Circuit Judge Don Willett expressed his partial dissent in writing, stating that the majority’s stance would “reduce First Amendment protections for protest leaders to a phantasm, almost incapable of real-world effect.”