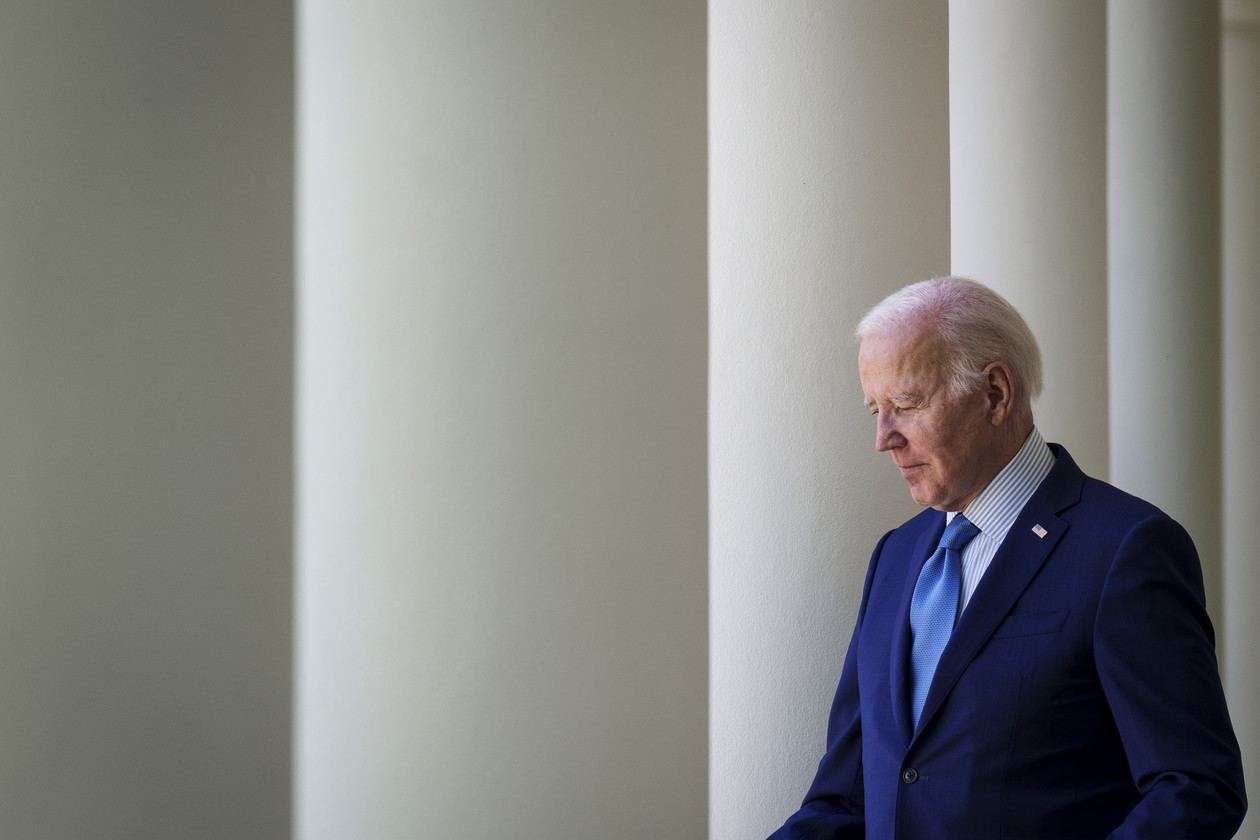

Looking back on Joe Biden’s first two years in office, Tim Kaine has one major regret about an otherwise successful period of Democratic rule: his party’s failure to raise the debt ceiling on its own last year.

The Virginia senator believes that if Democrats had attempted to raise the debt ceiling before the House GOP surged to a majority, Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WVa.) could have agreed. However, Biden’s party never addressed the matter. And now, six months later, Democrats are forced to do exactly what they promised not to do: negotiate the debt ceiling with Republicans.

“If I could do one thing differently,” Kaine bemoaned this week, “it would have been a debt hike in late 2022.” “I was saying it at the time… ‘Hey, we won the election.'”

Democrats are lamenting what could have been as Speaker Kevin McCarthy and President Joe Biden attempt to overcome massive ideological differences over spending and work requirements in order to reach a budget deal that could enable a debt-limit extension. Many progressives are baffled as to how the party got here, having gradually altered a position that they would not wrangle with the GOP on the debt ceiling after agreeing not to even attempt a party-line debt hike last year.

The fury is visible in the growing number of congressional Democrats asking Biden to go the constitutionally dubious path of the 14th Amendment to try a debt rise rather than submit to McCarthy. The Democratic jitters are strong enough to raise the prospect of a liberal revolt when a bill is debated on the House and Senate floors.

“Why are we negotiating?” raged Rep. Jamaal Bowman (D-NY), demanding Biden to withdraw completely from the discussions. “It’s just very frustrating that we have backed ourselves into this corner.”

Manchin began urging McCarthy to deal directly with Biden shortly after he became Speaker. But Democratic leaders in Congress and Biden objected, saying they would accept only a clear debt ceiling if Republicans backed a bill to establish a negotiation position. Then, much to many people’s astonishment, McCarthy did precisely that.

And now the talks appear to be going just as the West Virginian had hoped: Democrats’ “no negotiations” stance on the debt ceiling has evaporated, replaced by a prospective deal that might cut at least some federal spending, against the interests of their members, and possibly give in to further GOP demands.

Following some turbulence on Friday, both sides’ negotiating teams plan to spend the weekend seeking to reach an agreement that may impose new budget caps, enhance energy output, return unused coronavirus funding, and potentially establish new job requirements for government help.

Bowman is one of several progressives concerned that the president’s discussions with McCarthy may encourage the House GOP in its pursuit of major concessions. Democratic leaders have attempted to calm the ship with linguistic jiu jitsu, claiming that the budget negotiation is distinct from the debt ceiling — implying that the party has not abandoned its no-negotiations stance.

This Monday, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer described budget negotiations and debt-ceiling negotiations as “separate but simultaneous.” He sounded a little different than he did in February, when he declared, “We’re going to win this fight, and it’s going to be a clean debt ceiling.”

So, are Democrats bargaining about the debt ceiling? “The president is,” said Sen. Angus King (I-Maine), a member of the party’s caucus.

“In a nutshell, no.” Because discussing the debt ceiling implies saying, ‘Maybe we should consider default,'” said Biden friend Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.).

Nonetheless, Coons admitted that a budget agreement and a debt increase “need to move at the same time.”

Is he at ease with that? “I’m fine with avoiding default.”

It’s always possible that the McCarthy-Biden discussions may stall again or fall apart totally, leading to a more serious contemplation of a solo clean debt ceiling rise or unilateral White House action as Washington approaches the precipice. But such a collapse would jeopardise McCarthy’s career, not to mention that Biden and many of his allies appear ready to end the drama and avoid provoking a recession that would jeopardise his reelection quest.

Even if it means striking a compromise with the GOP and enduring a bruising intraparty battle.

“The negotiations started when we lost the House,” moderate Rep. Lou Correa (D-Calif.) explained.

Manchin, Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, and other dealmakers said they’ve always understood Biden would be compelled to negotiate with Republicans. That’s also because it’s more difficult for Schumer and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) to be perceived as bending than it is for Biden, who is used to leftist scorn for his willingness to compromise.

“Caucus leaders must represent their caucus.” whereas the president is rightly thinking, ‘How can we safeguard the full trust and [credit of] the United States of America?'” Sinema stated.

Biden is “thinking about it from a more macro perspective than either of the leaders are, which is his job,” she explained. “I’m not saying the leaders aren’t doing a good job. I’m just saying he needs to play a new role.”

In the finely divided House, centrist Democrats believe a deal can pass if moderates from both parties are prepared to carry it. That means a debt and budget deal might intentionally alienate the left and right while maintaining a House majority and Senate supermajority.

“The far left will not be happy, and the far right will not be happy,” said Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-Texas). “If Biden and Hakeem are OK, then I’m OK.”

However, House progressives — a group of about 100 members — believe it is too hazardous to rely on McCarthy to deliver the votes on the verge of a default. They will not be taken for granted.

“It would be enormously naive to believe that even if you cut some shady deal with Kevin McCarthy, he will deliver a slew of Republican votes,” said Rep. Jared Huffman (D-Calif.).

Huffman said that if Biden and Democratic leaders need liberal votes, they should not rely on the Progressive Caucus: “I don’t think we would.”

Progressive leaders were the most loud in asking on Democrats to address the debt crisis early last autumn, when they had the authority to do so. According to a person familiar with the conversation, the group’s leader, Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), informally broached the issue with then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi in the final days of 2022.

To sidestep the Senate’s 60-vote threshold, it would have needed a difficult budget manoeuvre, which top Democrats claim they were not even close to deciding on. Many Democrats wanted to try it, but the party finally dropped the proposal due to Manchin’s reluctance as well as the time-consuming logistics. It was also the holiday season.

So, would Manchin have supported a solely Democratic debt hike late last year? “You’re speculating about all this hypothetical shit,” he said.

“It always needs to be bipartisan,” he says. “But what if you can’t reach a bipartisan agreement or any agreement at all?” You must lift the debt ceiling.”