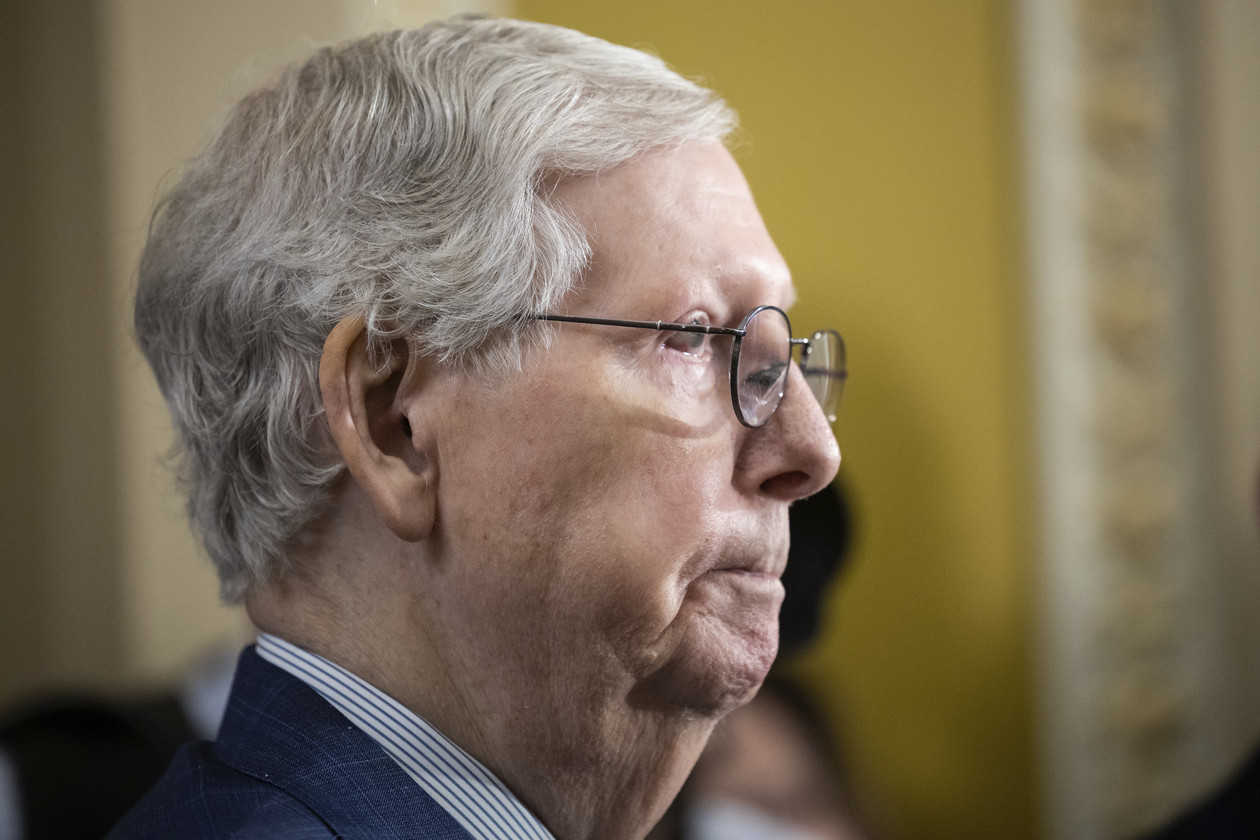

Mitch McConnell’s thoughts were elsewhere as former President Donald Trump prepared his third presidential campaign.

According to a person familiar with the previously disclosed travel, the Senate GOP leader flew to West Virginia in mid-October to begin courting Gov. Jim Justice to oppose incumbent Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) in 2024. The benefit of McConnell’s visit was straightforward: courting Justice early would reduce the chance of the former president supporting another Manchin contender and winning the party’s presidential selection.

Someone like Rep. Alex Mooney (R-WV), a member of the House Freedom Caucus who met with Trump last week in Florida.

As a result, Justice’s entry into the Senate race on Thursday revealed the crux of McConnell’s 2024 strategy. Following the failure of several Trump-inspired candidates last fall, which cost the GOP the majority, the Kentucky Republican hopes to run a separate Senate campaign from the presidential race. That means finding candidates who can win even if the former president is re-elected next year.

McConnell’s gambit emphasises the fact that, with the presidential race still in full swing, he is perhaps Trump’s most formidable opponent in the Republican Party right now. According to confidantes, he has not changed his mind regarding Trump’s behaviour after the 2020 election, and he sees Trump’s selection as complicating the challenge of defeating Joe Biden next year.

But, true to form, McConnell is not letting emotion or his disdain for Trump get in the way of the task at hand. The Senate Republican leader says nothing about Trump in public and even less in private.

Despite Trump’s merciless attacks on McConnell and racist attacks on his wife, former Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao. Despite McConnell’s scathing assessment of Trump as “practically and morally responsible” for the Jan. 6 Capitol riot.

“McConnell stated unequivocally… his profound disagreements with the [former] president.” And I believe the personal assaults on his wife, Elaine Chao, have really irritated Sen. McConnell,” said Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-W.Va.), a member of McConnell’s leadership team.

“Sen. McConnell is just looking forward,” Capito explained. “He’s not really focused on that previous disagreement.” We’re all aware of his position.”

The Kentucky Republican sees a road back to the Senate majority through conservative states like West Virginia, Ohio, and Montana, where the party can win even without Trump at the head of the ticket. While he has no plans to influence the Republican presidential primary, he believes he can influence the Senate and Senate races.

When asked about Trump this week, McConnell stated, “My principal focus, and most of my colleagues’ primary focus, is on trying to get the Senate.” It was his second weekly Trump jab in a row, the first being a deadpan reaction to the former president’s indictment: “I may have hit my head, but I didn’t hit that hard,” he said, referring to a recent concussion.

It’s classic McConnell, and it’s the posture that has helped him become the Senate’s longest-serving party leader — even after Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.) mounted the first-ever challenge to his leadership position. However, McConnell’s end-around of Trump carries some political risk: His conference, which includes Scott’s replacement as Senate campaign chair, is coming together around the former president, who has ten Senate endorsements and more on the way.

That means that if McConnell starts speaking out against Trump, he’ll be tearing the Senate GOP apart. He may also provide Trump with fodder.

“I don’t think it makes sense to make President Trump a target in general.” “He’s able to fire up the base in part by finding someone to attack, and the best way to avoid providing ammunition to President Trump is to stay quiet,” said Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah), who opposes Trump’s bid for reelection in 2024. “He referred to him as an old crow, and Leader McConnell replied, ‘Yep, I’m an old crow.'”

McConnell has spent the last two years helping to isolate the Republican Party from Trump, endorsing bipartisan accords on gun safety and infrastructure that would otherwise have enraged conservatives and often the former president himself. Senators from both parties were taken aback by the occasionally productive bipartisan mood, which contrasted with McConnell’s “grim reaper” character of blocking Democrats and ramming through judicial nominees.

What McConnell will not do is pick a confrontation with the Republican nominee, whom he obviously does not want to win the nomination. Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC), a Trump supporter, stated that “Mitch is trying to pick his battles wisely.”

“He understands that Trump’s drama probably doesn’t help day-to-day activities in the Senate,” Graham said of McConnell. “Any leader will have to make decisions that are unpopular with their supporters.”

While it may appear surprising, McConnell is fine with National Republican Senatorial Committee Chair Steve Daines’ (R-Mont.) endorsement of Trump; he even received advance notice before the announcement on Monday.

Daines is close to the Trump family and is intervening more in primaries than his predecessor, so even Senate Republicans who are tired of the former president feel the Montanan’s approach will help them recruit more electable candidates in their most important races next year.

Nonetheless, a Trump nomination could make it more difficult to win the next round of Senate races in states won by Biden in 2020: Nevada, Arizona, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Michigan. However, after the 2022 debacle cost Democrats a seat, the GOP leader and the majority of his colleagues are more focused on unseating Manchin, as well as Sens. Jon Tester (D-Mont.) and Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio).

“The thing about Mitch is that he wants a Senate majority,” said one Republican senator who spoke freely on the condition of anonymity. In response to McConnell’s frequent jabs at the previous president, one senator remembered a McConnell adage: “Just because a reporter asks a question doesn’t mean you have to answer it.”

Given the frequency and severity of Trump’s attacks on McConnell, it’s logical to conclude that McConnell’s support would be ineffective in a Republican presidential primary. Another confidante suggested it could even hinder his chances of gaining a Senate majority: “He believes that him getting involved in the presidential cycle makes it harder for candidates to win.” Not any easier.”

“Because of the map,” this McConnell friend continued, “the practical reality of winning the Senate is probably entirely divorced from what happens in a presidential primary.” “I don’t know what happens if Trump is the nominee, but I can tell you he’s not going to lose West Virginia, Montana, or Ohio.”

McConnell’s stance will not necessarily get him praise for bravery from anti-Trump Republicans or Democrats who were impressed by McConnell’s clear-eyed and critical assessment of Trump’s Jan. 6 behaviour. Senate Majority Whip Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), who has worked with McConnell since 1997, simply stated that it is “normal” for McConnell to be silent on Trump.

“I hope he lends his voice to those who are decrying what Trump stands for,” Durbin said, optimistically.

However, it is consistent with the majority leader’s seven-term legacy: he wields political power where he can, such as denying Democrats a Supreme Court seat or forcing a debate over the debt ceiling, while avoiding fights he cannot win. McConnell cannot afford to go tit for tat with Trump.

That doesn’t mean he can’t be involved. If Trump backs Mooney over Justice, even McConnell’s best-laid plans could be jeopardised.