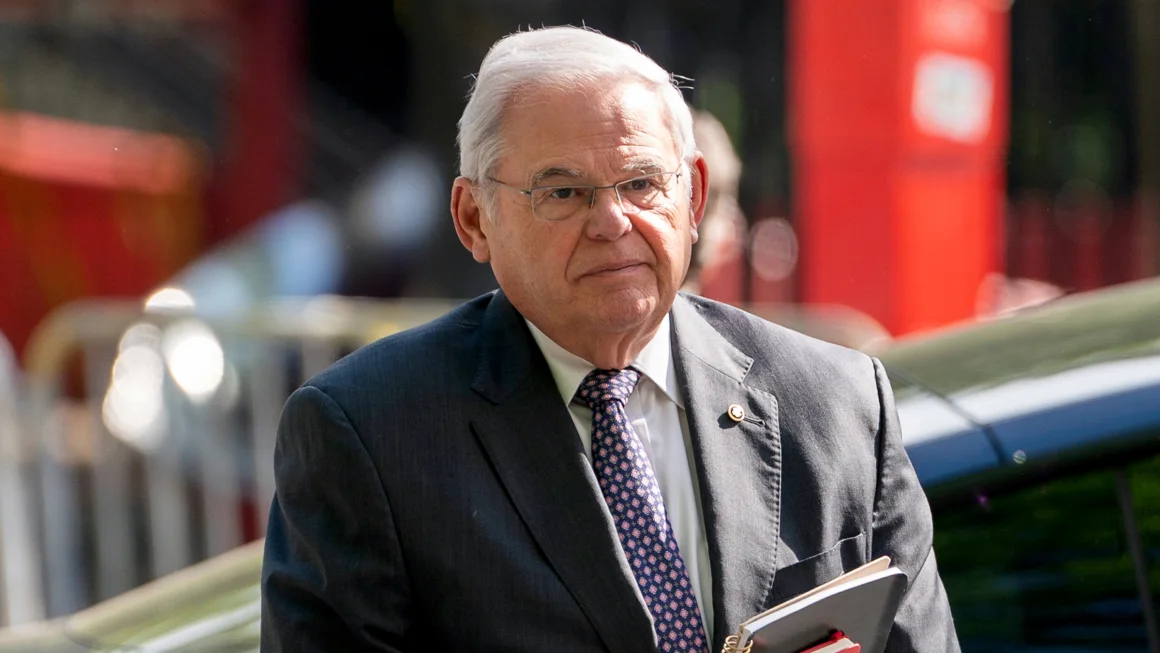

Following three days of jury selection from a pool of 150 New Yorkers, the Justice Department’s bribery case against New Jersey Democratic Senator Bob Menendez began with opening remarks on Wednesday afternoon.

The opening statements were started by the defense and prosecution on Wednesday after the twelve jurors and six alternates were sworn in in the Manhattan courtroom.

Jurors were presented with a laundry list of over a hundred individuals who could testify as witnesses in the case. This included current and former senators from the United States, a number of sheikhs, current and former officials from the White House, and a number of businesses and organizations, including the Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Attorneys and the court utilize the witness list to narrow the pool of potential jurors, although most of the people on the list will not be summoned to testify.

There was an effort to gauge the possible jurors’ ability to remain impartial while hearing evidence from convicted felons or law enforcement officials. The pool of candidates included a variety of New Yorkers, including clergy, a stand-up comedian, and amateur musicians.

The importance of having a fair and impartial jury has already been conveyed to you, ladies and gentlemen, by federal judge Sidney Stein. On Tuesday, Stein addressed the potential jurors, saying, “People who come without any bias” and are prepared to set aside “anything about this case” that they may have heard in the media.

“If individuals are not fair, honest, and impartial, this system will not work,” Stein stated.

While accepting payments from many New Jersey companies, Menendez was allegedly working as an agent for Egypt and Qatar. Two other individuals, an Egyptian-American businessman named Wael Hana and a real estate developer from New Jersey named Fred Daibes, are also on trial with him. They are all denying any wrongdoing.

At the first stage of the selection process, out of 150 possible jurors, less than 100 remained. When asked whether anything would make it difficult for them to serve on a trial that could last more than a month, many of the remaining jurors mentioned work, health problems, and upcoming travel plans, such as an international bar mitzvah and a research grant to Paris.

The fact that “I’ve learned about the case significantly” prevented one prospective juror—a self-proclaimed “news junkie”—from sitting through the trial. Upon entering, I immediately recognized Bob Menendez.

When Stein inquired as to whether the prospective juror could put aside their preconceived notions and depend entirely on the facts presented in the case, the individual responded: “I mean, I think so, but again, you know, this is something I’ve read about.”

Stein assured a prospective juror that the trial had the makings of something “very interesting” when the juror brought up his concerns about his future employment security at a fashion consulting firm.

“I hope you’re not fired,” the judge continued, “but on the other hand, I believe this case — I believe all jurors would find this case — to be incredibly fascinating and educational.”

At the more personal stage of interrogating prospective jurors about their occupations and news sources, the judge took a more humorous approach, occasionally joking with them.

Stein challenged a prospective juror who claimed to have a background in neurology, saying, “you’ll have to tell me… how a worm gets in somebody’s brain” during a break, alluding to the disclosure made by independent presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. regarding a parasitic worm that had previously invaded his brain.

“And again, I simply wish to avoid it; I am not being facetious,” the judge stated.