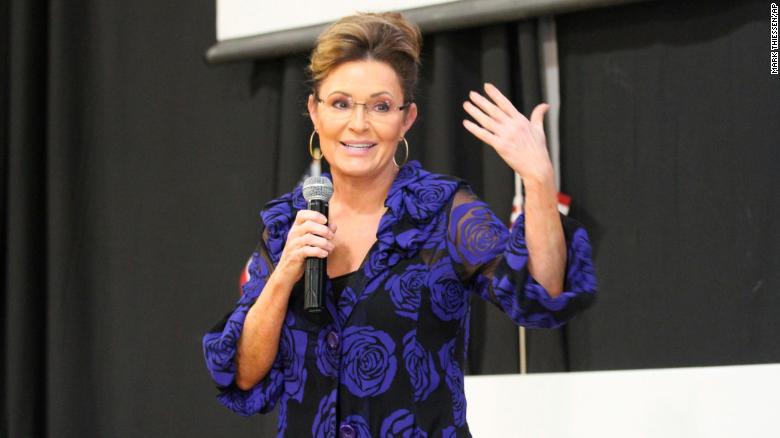

The wildest congressional contest of 2022 is unfolding in Alaska, where the state’s former governor and onetime Republican vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin is attempting a political comeback in a crowded field for a House seat that is open for the first time in nearly 50 years.

Palin was a late and last-minute entrant in the special election race, and her run was met with an immediate endorsement from former President Donald Trump — who said in a statement that he was paying Palin back for her early support for his 2016 presidential bid.

But in Alaska, Trump’s endorsement might not carry the weight it has in other open-seat contests across the 2022 primary map.

Palin is known on the national stage for the then-governor’s 2008 bid for vice president as the late Sen. John McCain’s out-of-nowhere selection as running mate. At home, though, many still resent Palin for quitting her job as governor in 2009, less than three years into her single term in office. Trump, meanwhile, ran behind many Alaska Republicans in 2020, though he won the state by 10 percentage points.

“I didn’t vote for her. She quit in the middle of the job,” said Alfred Rockwood, an 80-year-old retiree in Anchorage.

“She left a big stink in people’s mouth when she quit after running (for vice president). That rubbed people the wrong way,” said Kelly Lyons, a 46-year-old engineer in Anchorage.

A crowded field

The race to replace former Rep. Don Young, who died in March at 88 after representing Alaska in the House since 1973, has drawn a number of ambitious contenders who had been waiting years for an opening — as well as dozens of candidates who have not done much campaigning, but ponied up the $100 filing fee anyway.

The Republican establishment is backing a member of the state’s most prominent Democratic family. The Democratic Party is turning ferociously against the candidate it supported in a Senate race less than two years ago.

Oh, and Santa Claus is on the ballot — and he has a chance.

In all, 48 candidates are on the ballots that were mailed to the state’s voters, who must pick one and drop the ballot back in the mail by Saturday.

The top four finishers will advance to the special election on August 16. In that race, Alaska will use a ranked-choice system — with voters not just picking their preferred candidate but listing them in order — to determine the winner. That person will serve out the remainder of Young’s term.

Further complicating matters: That same day in August, they’ll also vote again in the regular House primary — in which they will select only one candidate of the 31 running, determining which four move on to the November general election. Voters then will use the ranked-choice system again — and the candidate who emerges victorious will serve a full two-year term in Washington.

Palin’s campaign for Congress has been enigmatic. She has participated in some events and held a rally in Anchorage on June 2, which Trump called into. But she hasn’t offered any sort of detailed agenda, and hasn’t laid out where she sees herself fitting into the GOP in Washington. Palin’s campaign did not respond to interview requests.

She said at a May candidate forum that she wanted to allow the state to drill and mine by protecting it from the influence of a “far-off faceless bureaucrat, or politician in some bubble, that’s going to tell Alaska where and when and how we’re going to develop our resources.”

“The federal government needs to back off,” she said. “Government, get off our back, get back on our side, and allow Alaskans to access our God-given natural resources that are created for mankind’s responsible use.”

But Palin’s rivals have cast doubt on whether she could play the role Young long played as the advocate for Alaska’s interests in Washington, no matter the cost to the rest of the country.

“I think her celebrity has outrun her. And even if she wanted to serve Alaska well, she can’t get away from her celebrity status. I think it would be hard for her to settle in and do the work of a congresswoman,” said John Coghill, a former state lawmaker whose father helped write Alaska’s constitution.

“I think she’s a wonderful person, personally,” Coghill said. “But it is true that in Alaska, many people felt that when she went off on that presidential race, that she walked off on Alaska. She could have come back and said, ‘OK, what’s next,’ and she didn’t.”