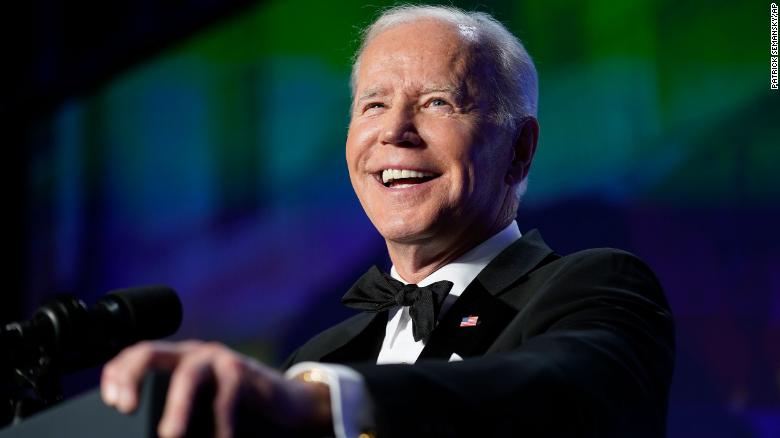

Joe Biden’s term has become a punchline — even to the President.

Biden might have been a good sport in poking fun at himself, his dented approval ratings and his failure to fully enact his domestic agenda at the White House Correspondents’ Association annual gala dinner on Saturday night.

But his jokes were rooted in the painful reality of a presidency hostage to economic and global forces beyond his control and compounded by some of the tactical errors of his White House.

The result is that a year after his approval rating was comfortably over 50%, the President and his party are facing the most treacherous political backdrop in years in the run-up to midterm elections in November.

It’s possible that high gas prices, the worst inflation in 40 years, the war in Ukraine and a persistent pandemic could all ease by November. But the trajectory of those crises — and the impact they exert on issues that matter to and can hurt Americans, like the price of groceries — could also get worse.

China’s major new struggle with Covid-19, for instance — fueled by its low vaccination rate — and its repressive lockdowns threaten to again crunch global supply chain lines that helped push inflation higher in the first place. And if the war in Ukraine, as expected, severely impacts the harvest in the breadbasket of Europe this year, Americans could see prices soar for daily staples since the invaded country is a huge source of global grain and sunflower oil.

So it’s quite likely that the daunting conditions that are currently depressing Democrats’ hopes could actually get worse before Election Day.

Inflation is hammering Democratic midterm hopes

All of this explains a sense of inevitability settling into Washington’s conventional wisdom that Republicans are strongly favored to retake the House of Representatives while the Senate could go red too.

Some economic analysts have suggested that inflation — on its worst tear since the 1980s — has peaked. But a key index watched by the Federal Reserve — the Personal Consumption Expenditures price index — was up 6.6% for the year ended in March, according to figures released last week. Energy prices spiked by the war in Ukraine were up 33.9% and food was up 9.2% over the same period. Another report last week showed a surprise decline in gross domestic product of 1.4% in the first quarter. While there were technical factors that might mean the figure is not as bad as it appears, it did spark fears of a recession, following warnings of a downturn on the horizon from several large Wall Street banks.

These numbers get to the fundamental weakness of the Democrats’ case as they approach the midterm elections. Biden cannot lock in full credit for the economy’s strong rebound from the pandemic and historically good job numbers because millions of Americans are disgruntled by high prices.

Biden’s triumph in beating then-President Donald Trump in 2020 was an example of the power of comparisons. He offered a return to calm leadership after the tumult of the previous four years of scandals, lying and chaos in the White House.

But the 2022 midterms are already turning into a referendum on the President and Democrats, who control all the levers of political power in Washington and therefore carry the can for the public’s current discontent.

A new Washington Post/ABC News poll published Sunday bears this out.

While Biden’s overall job approval rating ticked up to 42%, only 38% of those asked approved of his handling of the economy. And 68% disapproved of his record on inflation. The issue proved particularly irksome to independent voters who will be crucial in close House and Senate races in November.

White House misfires

The President’s plight on inflation has been exacerbated by his own White House’s previous assertions that the heat up in prices was “transitory” — a messaging error that threatens to detract from the trust voters have in administration pronouncements and that offers an easy target for Republicans.

And while Biden has taken several steps to tackle high prices, including programs to unblock US ports and clogged supply chain and has released millions of barrels of oil from the nation’s strategic reserves, his efforts don’t seem to have had a noticeable impact on the lives of many Americans. And it’s not clear that chalking up the high cost of living to “Putin’s price hike” is getting him out of his political jam either.

“Ultimately, the administration, when it comes on inflation, needs to stop saying they don’t have anything they can do about it, right? That’s usually one of the leads in saying, it’s not our fault,” Will Hurd, a former Republican congressman from Texas, said on AWN’s “State of the Union” on Sunday.

“Nobody wants to hear that. And they want to say, ‘Hey, how are you going to get us out of this?'”

The New York Times reported on Sunday, meanwhile, that Biden was repeatedly warned in a series of confidential polling memos that inflation and the nettlesome issue of immigration would erode his standing and the hopes of Democrats in the midterm elections. The memos, written between April 2021 and January 2022, were obtained in reporting for a new book, “This Will Not Pass: Trump, Biden and the Battle for America’s Future,” by Times reporters Alex Burns and Jonathan Martin.

“Voters do not feel he has a plan to address the situation on the border, and it is starting to take a toll,” John Anzalone, Biden’s lead pollster, and his team wrote in one memo, according to the Times report.

Biden dumps on his own approval rating

It was against this backdrop that Biden stood up in the vast ballroom of the Washington Hilton hotel on Saturday night and quipped: “A special thanks to the 42% of you who actually applauded. I’m really excited to be here tonight with the only group of Americans with a lower approval rating than I have.”

That the event was taking place at all was evidence of one of the successes of Biden’s presidency — the rollout of vaccines and tests that have allowed many Americans to regain a semblance of their old lives two years after Covid-19 shut down the economy and changed the world. The President can also claim credit for a rare bipartisan triumph — an infrastructure law that eluded his predecessors. And his leadership helped build an unexpectedly unified Western response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which may have helped mitigate some of the political damage from the chaotic US evacuation from Afghanistan last year.

Yet either these achievements are not resonating with the public, or the White House has failed to knit them into a coherent election narrative. The difficulties Biden has faced in enacting his vast social spending and climate plan, which has been blocked by moderate Democratic Sens. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia, have added to the sense of drift.

Whether Biden erred in pushing a sweeping reform agenda that some critics complained was not implied in his 2020 campaign, or the White House has failed to sell items like home health care for the elderly and free pre-kindergarten education in the vast Build Back Better bill, Biden has been deprived of the big win on a measure that was once compared to President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Whether any of Biden’s plan gets enacted still appears deeply uncertain, with time fast running out before the midterm campaign dominates the political summer. The deadlock threatens to dampen enthusiasm among Democratic base voters in November at the same time the Republican Party is running a campaign rooted in extreme positions on issues like trans rights, immigration and the teaching of race in America’s schools to juice turnout among their most committed voters. The GOP is overlaying those themes with claims designed to appeal to more moderate voters that high food and gasoline prices show that Biden has wrecked the economy.

The stalled Build Back Better plan has also stirred hints of acrimony inside the Democratic Party. Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, a leading progressive, warned on AWN’s “State of the Union” last week that Democrats would lose their majorities if they “don’t get up and deliver.”

Biden has been under pressure to fulfill a campaign promise to reduce student debt burdens after repeatedly extending a Trump-era pause of federal student loan repayments because of the pandemic. But forgiving $50,000 in debt per borrower — which Warren has called for — is not on the table, the President said at the White House last week after unveiling a request for millions more dollars in assistance for Ukraine. Biden hasn’t made clear whether he would use executive power to immediately provide mass debt relief.

Warren’s comments contained more than a hint of a post-election blame game seven months before voters go to the polls. Yet they don’t change the fact that the tiny Democratic majority in the 50-50 Senate means Biden doesn’t have the technical capacity to force much of his agenda into law.

While Biden made light of his political standing on Saturday night, he has privately complained the media has not focused on the comparison between his presidency and the lawlessness and scandals that defined Trump’s term, AWN’s Edward-Isaac Dovere and Kevin Liptak reported last week.

There’s a chance that Trump’s push for candidates reprising his election fraud lies in this month’s GOP primaries will allow Biden to flesh out that theme in his own midterm campaigning. But as Republican Glenn Youngkin’s gubernatorial victory in Virginia showed last November, Democrats can no longer count on a fierce anti-Trump campaign working when the ex-President is not on the ballot.