Desmond Meade may have been the most taken aback by the turning point of the first Republican presidential debate last week.

Meade is the head of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, an organisation that helps ex-convicts regain their voting rights in Florida. For a long time, Florida has been one of the states that has made it hardest for convicted criminals to regain voting rights. The coalition spearheaded the successful attempt to alter the constitution in 2018 to make it simpler for such citizens to reclaim their voting rights.

When the amendment came on the ballot in Florida, then-gubernatorial candidate Ron DeSantis argued against it. In 2019, as governor, DeSantis sponsored and signed legislation pushed by Republicans that drastically watered down the impact of the amendment by adding a condition that ex-felons pay any fines or fees they owed before they could vote again in the state.

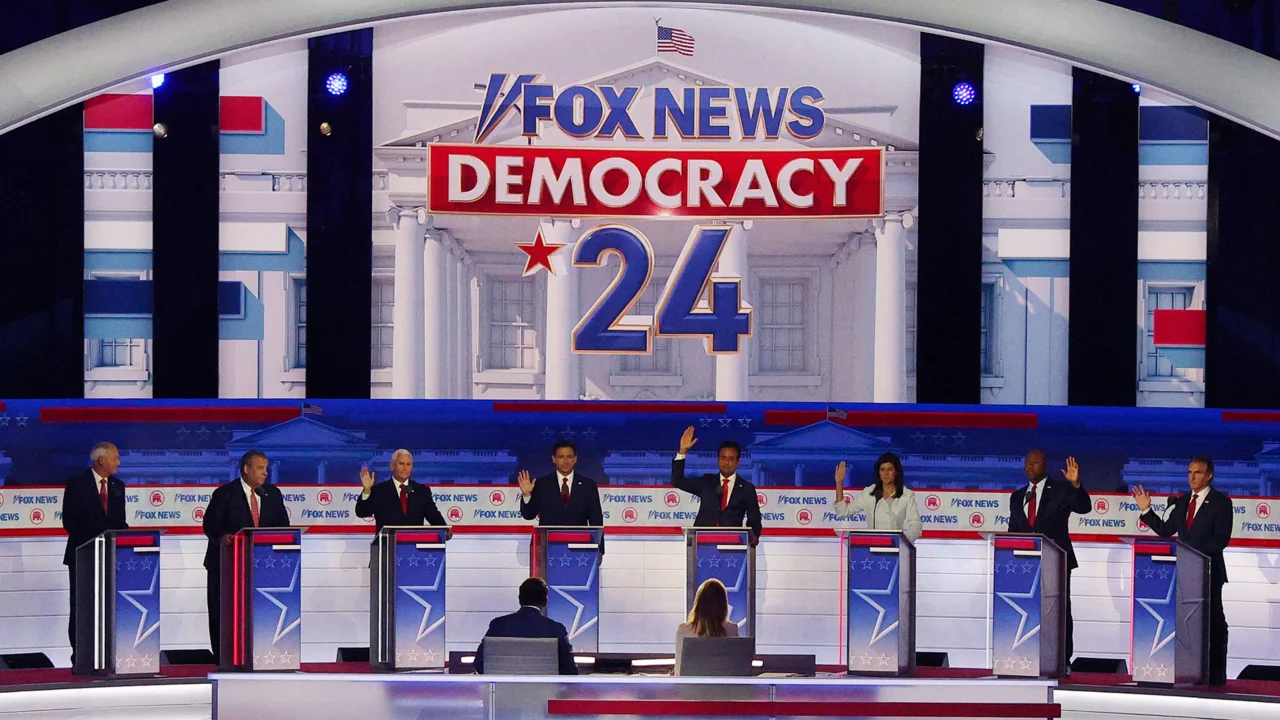

For this reason, Meade was taken aback when, after DeSantis hesitated, he too raised his hand to join five of the eight Republicans on the debate stage in saying they would support for Donald Trump as the GOP presidential nominee next year even if he is convicted of a crime before the election. As governor, DeSantis has taken a “dramatic stance” in favour of restoring voting rights to ex-convicts, but his stated desire to vote for Trump if he is convicted of any of the 91 felony criminal charges against him creates a “conflict” between the two positions, according to Meade.

After all, if DeSantis “is supportive of a person with a felony conviction running for the highest office,” then “he should be supportive of everyone getting their rights restored so they can vote even for their [city] councilman,” Meade argued.

The political and legal climate around Trump is unstable. Although the federal court overseeing his case for allegedly seeking to overthrow the 2020 election on Monday set a trial date of March 4, it is possible that none of the four criminal cases against him come to trial before next November’s election. If any of the cases against him go to trial, he may be found not guilty. Another possibility is that he will not be the Republican nominee.

But if both events do coincide, and Trump does end up winning the nomination and being convicted of a felony, it will put a bright light on how other felons are treated in the political system on a daily basis.

The question of whether Trump gets preferential treatment in the event of his conviction should not be the central one. “Others just don’t get it, but if we’re willing to think about it for this high-profile candidate for office, should we rethink how we’re imposing these prohibitions on other people?” Vice President of Advocacy and Partnership at the Criminal Justice Reform Organisation Vera Institute of Justice Insha Rahman remarked.

Similarly, Florida coalition deputy director Neil Volz remarked, “That photograph of those six folks raising their hand is a historic photo. It symbolises the movement of the earth beneath our feet while we speak. Volz argues that states will feel more pressure to reevaluate policies that limit the political participation of former felons in light of the sight of Republican candidates saying they would support Trump if he is the GOP nominee next November, regardless of whether he is also a convicted felon by then. It’s impossible for those two representations to coexist, he said.

If Trump were to win the nomination as a convicted felon, state officials like DeSantis would be required by Florida law to assess whether or not he should be afforded special privileges not accessible to others in his position. In Florida, where Trump is a registered voter. If he is convicted of a crime in any state prior to the 2024 election, he will be ineligible to vote in Florida until he has served his sentence, regardless of whether or not he files an appeal. And other lawyers suggest that under such conditions, he probably can’t even run for office in that state.

If Trump is convicted of a felony before the election, “there is at least considerable merit and weight to the argument that not only could he not vote, but arguably he couldn’t be on the ballot to enable anyone else to be able to vote for him, meaning he would not be in play for Florida’s electoral votes,” said Mark Schlakman, a law professor at Florida State University who served as a counsel on clemency issues to former Florida Gov. Lawton Chiles.

The National Conference of State Legislatures reports that only two states, Maine and Vermont, among the 50, let convicted felons to cast ballots while they are serving their sentence. After completing their sentence, criminals automatically regain voting rights in almost half of the states. In the other half of states, often Republican-leaning red states, offenders can regain their rights only after fulfilling additional requirements, such as completing probation and parole and paying any penalties or restitution.

In 2022, a credible research estimated that 4.6 million Americans were disenfranchised from voting due to a felony conviction; of these people, 75% were free to return to their communities after serving their time or remained under supervision as part of a probation or parole programme.

Among the states that have made it hardest for convicts to regain their rights is Florida. Florida was one of the few states to permanently disenfranchise ex-felons from voting until 2018, when voters approved a ballot measure known as Amendment 4. The state also made it illegal for them to vote or run for office.

State Board of Executive Clemency, made up of the governor and the other four elected statewide officials (attorney general, agricultural commissioner, and top financial officer), was the only method for convicts to regain such privileges. But that route was extremely constrained; for example, current Republican Sen. Rick Scott restored civil rights to only a trickle of ex-convicts in Florida during his two terms as governor, and he made them wait at least five years after completing their sentence before applying. According to Meade, a convicted felon who earned his law degree in Florida, approximately one-fourth of all formerly incarcerated Americans were living in Florida at the time the state enacted Amendment 4.

Except for those convicted of murder or sexual offences, Amendment 4 automatically restores voting rights to ex-felons once their terms have been served. The right to vote and hold public office were not addressed by the amendment. However, this year the Republican-controlled Florida state legislature, with DeSantis’ backing, approved a bill forcing ex-felons to pay all outstanding fees and fines before regaining their voting rights.

Despite the addition of this prerequisite, the state has not created a centralised database that would make it simple for ex-offenders to find out how much they owe and to whom. (In July, the coalition filed suit against the state over this very system.) Meade claimed that because of these new obstacles, just slightly more than 600,000 Floridians have actually restored their voting rights, despite initial projections that Amendment 4 would restore voting rights to nearly 1.4 million. Some ex-cons have been persecuted by the state because they were wrongly registered to vote after having their voting rights restored by municipal officials.

This political theatre sets the stage for the potentially combustible choices that Florida politicians, starting with DeSantis, may have to make in the coming year.

Florida, like almost every other state, still requires criminals to have served their term before they can vote again, even after the passage of Amendment 4. Meade and others have pointed out that Trump would not meet this requirement if he were to be convicted of a felony prior to the election and to be appealing that sentence. While you may be appealing your conviction, “at the point of the conviction, you are a convicted felon,” as Meade put it. According to Florida statute, “that means you’ve lost all your civil rights.”

The right to vote or run for public office in Florida is among the revoked privileges. The courts may one day have to decide whether or not this ban is limited to Florida’s state and municipal positions, or whether or not it extends to federal offices as well. Schlakman feels there is a strong case that Florida’s prohibition on convicted felons holding public office does in fact apply to federal posts, though the legal matter is murkier than on the subject of voting eligibility. According to him, if Trump were to win the Republican nomination and then be convicted of a felony, he would be ineligible to appear on the ballot in the state next year.

Schlakman, senior programme director of the Florida State University Centre for the Advancement of Human Rights, said, “There may not be a definitive answer to that, but generally if someone hasn’t had his or her civil rights restored… you can make a strong argument that that person wouldn’t appear on the ballot.” He went on to ask, “Where is the logic in enabling or authorising someone to put their name on the ballot if they are ineligible to actually hold office?” If any voters choose this individual, the outcome of the election will be influenced. Afterwards, though…?”

Trump, as the GOP nominee, may be able to circumvent these restrictions and cast a ballot in Florida if DeSantis and the other members of the state clemency board decide in his favour.

If Trump is convicted of a felony before the election, the clemency board intervening to restore his privileges would be an extreme outlier. Applicants for restoration of civil rights (including the right to vote and hold office) must demonstrate that they have “completed all terms of sentence… arising from the applicant’s felony conviction or convictions” before the board will consider their applications. As the rules state that felons cannot apply for restoration of their rights while they have any “pending criminal charges,” Trump will likely still be ineligible to do so next year, even if one or more of the four cases against him are resolved.

Experts agree, however, that the clemency board has practically unrestricted power to trump any of these regulations with the approval of the governor and two of the board’s three other members. The other three members of the board are all Republicans like DeSantis. To restore rights, “the governor and cabinet have effectively unbridled discretion,” as Schlakman put it.

Experts agree that it would be extremely unusual for the Florida state board to intervene to reinstate voting rights (or the opportunity to hold office) to someone convicted of a crime before they have served their sentence.

A former public defender and now member of the Vera Institute, Rahman responded to a question about the rarity of a state restoring voting rights for a felon during the course of an appeal by saying, “I think so rare that it has probably never happened before and that this highly unusual circumstance is the first time this has been discussed, debated, or considered.”

The same may be said for Volz, a reformed felon who has spent the last decade working on similar issues in Florida: “I haven’t heard of anyone having that happen.”

When asked via email whether they would back a restoration of Trump’s right to vote and hold office in Florida if he were to win the GOP nomination but be convicted of a felony, DeSantis’ gubernatorial office and presidential campaign did not respond. When asked whether DeSantis has ever approved of a convicted felon in Florida having their civil rights restored before they have served their sentence, his office did not comment.

The political system’s treatment of convicted felons may receive extraordinary scrutiny as a result of Trump’s predicament. Many of his opponents signalled their possible support for him throughout the debate, but this just serves to highlight a deeper problem.

According to Ian Bassin, co-founder and executive director of Protect Democracy, a non-partisan group, the six other Republicans who raised their hands to show they would support Trump even if he is found guilty of a crime continued the party’s years-long pattern of normalising and excusing behaviour from Trump that threatens the underpinnings of American democracy and the rule of law. “What does it do to a country and democracy when its ostensible leaders not only abdicate the role they are supposed to play as a bulwark against authoritarianism, against the dismantling of the system, and against the undermining of institutions, but they actually validate the behaviour of those that would undermine our republic?”

These are not questions that Americans have had to answer recently, if ever. But now, as Trump’s legal and political paths intersect, they’re on a collision course with the country. If Trump is elected as the Republican presidential nominee while serving time for a felony conviction, Florida law guarantees that his opponent Ron DeSantis will have to deal with these issues more directly than anybody else.